During the 17th century, virtually no other work had a cultural impact comparable to that of l’Astrée by Honoré d’Urfé. This 5,000-page novel in three volumes, the first of which was published in 1607, enjoyed immense success for over a century both in France and at numerous courts in other European countries. A sprawling narrative that amounts to something like an hommage to pastoral poetry, l’Astree tells of the shepherd Celadon’s love for his shepherdess Astrée. The two ideals of bucolic love and peaceful country life far off from town or court had a lasting influence on all of the arts practiced during this period. Exemplary of this effect are the musical genre of the air de cour and its successor, that of the air sérieux, which almost exclusively revolve around tales of pastoral romantic suffering. The first French collection of airs with figured bass ever printed, Michel Lambert’s airs of 1660, adheres consistently to this definition. The renowned singer and singing teacher was particularly adept at writing in this intimate song-form. As an enthusiastic attendee of the so-called ruelles, the worldly and literary bedchambers of high-ranking ladies, Lambert had developed a highly refined musical style. And he would later go on to assume responsibility for the vocal training of the singers in the magnificent opera performances led by his son-in-law, Lully. An equally fine champion of this song style was the less-known composer Sébastien le Camus. Also in the employ of Louis XIV’s court, Camus occupied the post of Surintendant de la musique du Roi. And parallel to this royal music in Versailles, Marc-Antoine Charpentier oversaw the intense musical life of the Hotel de Guise in Paris, the residence of his patron Marie of Lorraine. Today, Charpentier (who himself sang as an haute-contre) is known above all for his sacred music. But his secular output likewise contains precious gems that, even now, stand out for their gripping expressivity—thanks not least to his training under Carissimi in Rome, for which reason Charpentier is thought of as the most Italian of all French composers.

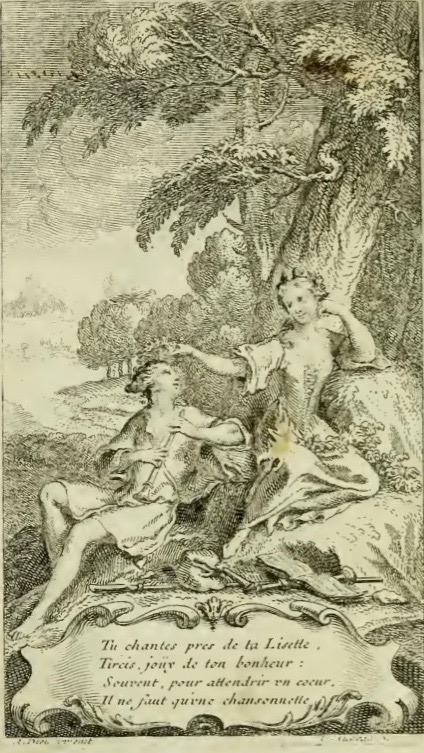

From around the beginning of the 18th century, the pastoral movement in music gave rise to a new genre: the brunette. It represented a new type of light, refined entertainment music, a genre thoroughly adapted to private use, that grew into a veritable fad. These little strophic songs were disseminated above all in printed collections and as periodically appearing works, with their composers seldom specified. The best-known such collection is the one put out by the publisher Ballard, of which the first volume was printed in 1703. The songs were published both in simple arrangements and in artfully embellished ones to account for the differing abilities of their performers.

In this program, we place our selection of airs and brunettes in the context of instrumental music from the same periods and musical circles. Louis Couperin (uncle of the more famous François), for example, was likewise employed at Versailles. There, this harpsichordist, organist, and treble gamba player served as ordinaire de la chambre du Roi in addition to his post as organist at the church of St-Gervais in Paris. A more mysterious figure is that of the Sieur du Sainte-Colombe, said to have been his era’s foremost master of the viola da gamba; today, we know him almost exclusively from his extant works. His large body of music for one and two viola da gambas makes him an important forerunner of Marin Marais.

Political decisions around this time entailed a certain opening of the French court, particularly to Italian influences. 1656, for example, saw Cardinal Mazarin invite an Italian opera troupe to Paris in order to have them perform L’Orfeo by Luigi Rossi. And it can be assumed that the Passacaille del Signore Louigi, preserved as part of an important French keyboard music collection from this era (the Bauyn Manuscript), likewise found its way to France thanks to this visit by the Italians. Also from Italy was the virtuoso theorbist and guitarist Angelo Michele Bartolotti, who had played in the famed ensemble of exiled Queen Christina of Sweden before, after various journeys (including to Innsbruck), he arrived in Paris, where he was to spend the rest of his life. Another guitar virtuoso, perhaps the greatest of his era, was the Italian Francesco Corbetta. With the guitar enjoying immense popularity during this period at the court of Versailles, he spent many years working in Paris during which he published two important collections of solo music for his instrument.

Brunette Le beau berger Tircis

Louis Couperin (1626-1696)

Simphonie

Marc-Antoine Charpentier (1643-1704)

Ah laissez-moi rêver

Michel Lambert (1060-1696)

Vos mépris chaque jour

Angelo Michele Bartolotti (1615-1681)

Passacaglia aus Libro Primo di Chitarra Spagnola

Brunette Félicitée passée

Luigi Rossi (1598-1653)

Chaconne

Brunette J’aime un brun

Pause

Louis Couperin

Fantaisie pour les violes

Sainte-Colombe (fl. 1678-1692) aus dem Tournus Handschrift (ca. 1690 verfasst)

Chaconne

Michel Lambert

Ma bergère est tendre et fidèle.

Sébastien Le Camus

Amour cruel amour

Francesco Corbetta (1615-1681)

Allemande

Louis Couperin

Prélude

Sébastien Le camus

Laissez durer la nuit

Anon.

Sans frayeur dans ce bois

Erik Leidal Tenor, Daniel Pilz Viola da Gamba/ Baroque guitar, Eugène Michelangeli Harpsichord

Brunettes from Brunetes ou Petits Airs Tendres… Tome Premier, Ballard, Paris 1703.

Music by Louis Couperin from the Bauyn Manuscript